Where do we stand? That’s always a good question, and as far as pictures go, they answer it for us. Including any kind of perspective into a picture means defining the audience’s point of view.

This aspect has always fascinated artists and audiences. Over the centuries, a lot of thought has gone into imitating what we perceive when we look at the world. There have been many attempts to make it easier for aspiring artists to construct mathematically correct perspectives ever since.

And then came photography, and with it, a machine for making perspectives without even thinking about it.

Without thinking about it – really? I am convinced it is a huge mistake for photographers not to think about perspective. And that’s especially true for toy photographers. Perspective plays a crucial role in deciding whether our beholders feel they are looking at the scene from a distance or if they see themselves as part of the scene.

Simply put, the camera is a stand-in for the beholder. So if you set up your camera in front of a toy figure that stands in front of a background – say, a wall -, that’s how the beholder will feel: like somebody standing on front of a figure that is standing in front of a background. This situation always reminds me of the theater; you have two separate spaces, the stage and the auditorium.

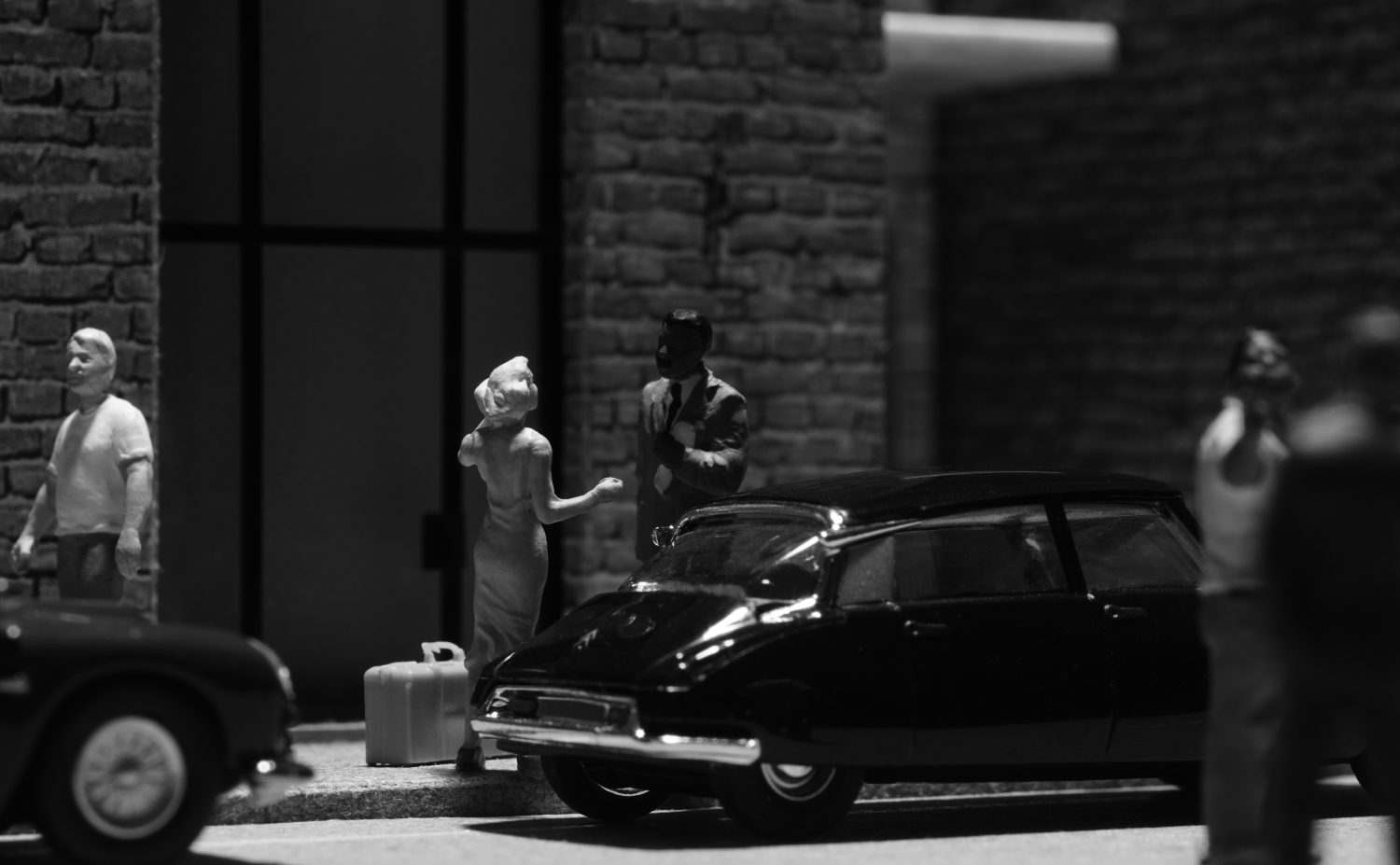

Now take your camera, set it up at the end of a miniature street and point it at the figure.

This positions the beholder in the street. This situation looks much more immersive to me; it rather reminds me of cinema. This explains why I like to put something into the foreground when I look at a building’s front from directly opposite.

All this concerns the horizontal positioning of the camera. However, as toy photographers we should also be well aware of the vertical camera movement. For the picture above, I have chosen the lowest camera angle possible. The beholder is practically lying flat on the belly. The picture might therefore be considered fictitious – though the low angle adds drama. Alternatively, the camera person could climb further up.

Does this detach the beholder from the action? Probably. That’s why I prefer being at eye level with my figures.

There is a simple way to do so: First, level your camera; everything should be parallel to the floor. Set up your figure, then add other figures, placing them closer to the camera and farther off. Then move the camera in a strictly vertical direction (without tilting) until all the figures’ eyes are on the same level.

In general, any line that runs into the depth of the picture and runs parallel to the horizon indicates the level of the camera – if you do not tilt it. For me, my figures’ eye level is usually the best camera position to start with.

This is an extra step, and I admit it can be a hassle. But I like to know where I stand. And I strive for giving you a chance to know where you (are intended to) stand, looking at my pictures.

Excellent explanation of perspective, Tobias, especially in relation to the toys and figures we use. Thank you!